Chapter 1 The Queen’s Party

To understand how the disappearance of Daniel Westcott bewildered the people of Tampa Bay, you would have to know that the city was much smaller then. More like a sleepy town, Tampa sprawled out and yawned along the edge of the Hillsborough River. In 1972, the largest shipping port on the Sun Coast had yet to attract a major cruise line or an NFL team. Some historians claimed the town’s slow growth and propensity to “keep to itself” could be traced back to the early 1930s and the failure of the Tampa Bay Hotel. Before that, beneath the hotel’s soaring minarets, cupolas, and horseshoe arches, the palatial palace on the river had attracted well-heeled families who escaped northern winters to play golf and shoot quail on the verdant grounds that surrounded the hotel. After sumptuous meals, they strolled along the rambling verandahs. Once the Great Depression hit, the hotel was abandoned, even ghostlike. Some people claimed the town turned inward then.

In the summer of ’72, before anyone knew Daniel Westcott was missing, Tampa’s summer routines ran along in the usual ways. Picnics were prepared and packed to shell the beaches of Treasure Island or fish along the causeway. Days lengthened, stretched out by heat. In town, the hot, bright sun of early June sent children to play in sprinklers, while adults lingered in the shade of granddaddy oaks, sipping lemonade and anticipating the summer’s one social highlight—the Gasparilla Queen’s Party. This annual ball, hosted by the new queen’s family, was the most exclusive event in the long line of Gasparilla festivities. It’s important to note that it was the patrician families of Tampa who had dreamed up these amusements and scattered them across the calendar year. Their intent was to enhance the town’s prosperity and to create a posh social niche for the founding members of the Gaspar Krewe and their families.

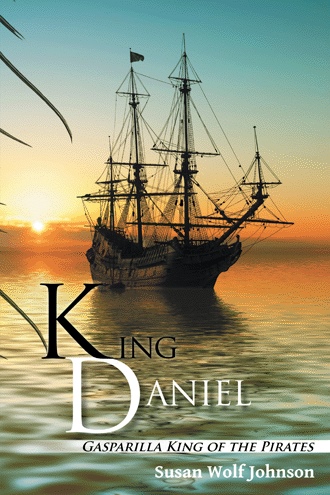

The grand town holiday, Gasparilla Day, was seeded in the glory years of the ill-fated hotel and was rooted deeply within the locals’ imaginations. It came to full flower through the decades. Based on a mythical pirate and fashioned after New Orleans’s Mardi Gras, Gasparilla thrilled the townspeople with an annual pirate fest that paraded down Bayshore Boulevard. Before Tampa hosted Super Bowl XVIII, the celebration was held on the first Monday of February. Banks closed, schools shut down, and businesses locked their doors for the day. Even the mail was held so everyone could enjoy the parade. From convertibles at the head of the motorcade, local celebrities waved as high school bands marched and played John Phillips Sousa. Elaborate floats glided in the procession were identified as TECO, GTE, or Freedom Federal. But the most thrilling float—the one the townspeople most heartily cheered—was the royal float. Two thrones centered the moving pageantry and carried the king and queen of Gasparilla, who waved graciously to their loyal subjects. On that day, painted Gaspar pirates walked the parade route. They threw beads, fired blank ammunition from .38-caliber revolvers, and kept pace with the day’s main event—heavy drinking. Everyone, young, old, and infirm, embraced the merry event. But the Queen’s Party was held for krewe members only.

On the eve of June 10, Gaspar pirates escorted their ladies through the double doors of the Tampa Yacht Club. They could hear the orchestra playing, “Days of Wine and Roses,” as the much-anticipated gala began. Women in elaborate gowns graced the ballroom. They toasted one another with grasshoppers and tequila sunrises, drinks as brightly colored as the gems around their necks and wrists. Costumed in plumed pirate hats, the men smoked cigars and downed Harvey Wallbangers. The french doors were open. Couples glided from the ballroom to the verandah outside to dance beneath the waning crescent moon. They waited patiently for their king. Attuned to his big-hearted laugh, they knew it would announce his arrival. At six foot three, Daniel stood above every crowd. With an impressive shock of black hair and a pair of curly eyebrows to match, he wouldn’t be missed as he kissed his way across the ballroom or threw an arm across a pirate’s shoulders. Despite his sixty-eight years, Daniel would dominate the dance floor in a light-footed foxtrot or a sassy swing. The Krewe of Gaspar drank, danced, and chatted, while the night ticked on. They danced until the moon disappeared behind the live oaks and until the band played its last song.

But King Daniel did not arrive.

Because Daniel was not found for almost a month, stories from that summer had taken on a curious twist. Passed on in ways that are difficult to trace, the details of what actually happened remain debatable, although the outcome was hard fact. A couple of pirates later swore that Daniel was headed for trouble in the worst way. Others said they never saw it coming. What everyone agreed was how the town rallied to help the Westcott family. After all, with Daniel missing, his wife, Natalie, was all but alone in that big house. She had an elderly family retainer there, but now the roles were reversed. Natalie had become Eula’s caretaker. Eula’s daughter, Niobe, worked there too, but her duties were focused on Natalie’s daughter, Julia, whom most agreed was more than a little “touched” in the head.

At the time, Julia was in her late forties—and everyone knew that. At age twenty-two, she’d worn the queen’s crown and ridden the float. She’d then married a man named Richard McNeil, who worked for Tampa Electric. He was, of course, a pirate in the krewe. Around the time their first child started school. Julia took to her bed. Some called it migraines. But wait—for the sake of clarity, we must return to the night of the Queen’s Party and what happened then.