The wind filled the sails. Sketty Belle charged along, bouncing and leaping and loving the movement. The creak of tight sheets and halyards, timber gaffs and booms straining and releasing as the air relaxed was part of the escalating cacophony. The clatter of the wooden sheet blocks as they lifted and fell on the deck. I could almost hear voices in the rigging, in the wind. But there was no-one else on board.

This passage took me seventeen days. Alone. Alone on my small sailboat. On a voyage from Mauritius, a jagged tropical island in the south-western Indian Ocean, towards South Africa. I was twenty-seven, pursuing adventure, and I had it, condensed into this moment of time.

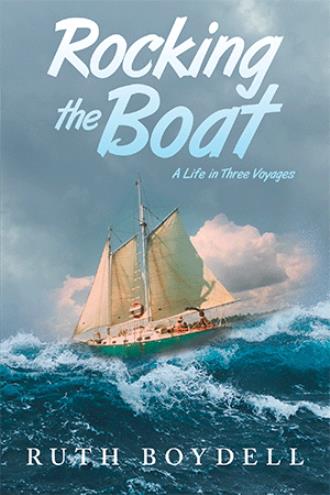

Sketty Belle was a thirty-foot-long steel gaff-rigged schooner, a theatrical-looking darling of a sailboat. Shapely, strong, and sturdy. Simple. An oceangoing small ship. My dream boat.

I sailed this tiny vessel from Australia, but this was my first long sea passage on my own. I had “run out of crew” as my first mentor, Colin, foretold. “It is inevitable, lass,” he advised me. “Not everyone will want to follow your dream or has the willingness to sail an ocean passage on a small craft.”

I had left northern Australia with my brother and his girlfriend as crew. They got seasick and jumped ship at our first port, Christmas Island. I then ‘borrowed’ a crewman, Richard, from another boat. He had his own journey to fulfill and left after several months, when we arrived in India. My most recent crew had been a journalist with an assignment to visit a remote military base in the mid-Indian Ocean. I was thrilled to be part of that mission. He and I were destined to sail together on later voyages. But at this time, I was alone.

I had these days of solo sailing to learn how to live with myself emotionally, spiritually and physically.

Emotionally I shut myself down. I read many books. I wrote to my friends. I did the barest necessary for navigation. I fed myself. I slept when I could, in twenty-minute bursts at night so I could check for shipping. I saw the sky and sea in its beauty but found it hard to revel in its glory. I sat with worry.

Spiritually I was only beginning to glimpse my insignificance in a very large universe. It was humbling.

Physically I waited until I needed to act. I didn’t yet know if I had the nerve to go on deck in heavy conditions to reduce sail, and haul those sails up again when needed.

So, I sat in fear. It was enervating. Draining of all motivation. I was a frightened woman alone at sea.

I had no radio except for a receiver someone had kindly lent me. It wasn’t for lack of preparation. It was my beliefs about my priorities. People have sailed around the world with less equipment. I was following those singlehanders of yore. Joshua Slocum, first solo circumnavigator, whose greatest technology was a wind-up clock. Bernard Moitessier, French sailing icon, who carried very little in the way of technology, a small engine. Colin Usmar, my first skipper, total sailing romantic, who had even less equipment than Moitessier.

I carried a sextant, a compass, a nautical almanac and calculation tables. GPS was called SatNav, and certainly not widely available to the likes of most yachtspeople in 1983. The cost was an exorbitant $12,000. Given my boat cost me $16,000 Aussie dollars a few years earlier, you might feel my reluctance! I also had the luxury of an engine, two batteries and a small solar panel.

I tried playing music on my cassette tape player once I charged the battery fully using the unreliable alternator. A mixed tape a friend had made. I couldn’t listen long. It was too evocative of my aloneness. It was just me and the boat and the noise of the wind and sea and the cabin and the enormously comforting clicks and whistles of dolphins around Sketty Belle at night.

Noises below deck began to increase. The pot on the gimballed kerosene stove rocked on its metal base. Clink. Clunk. Clink Clunk Clang. Cans of food, pots and pans, and the plates and bowls in the lockers began their orchestral warmup. I attempted to silence the noisy cupboards filled for this long stretch at sea with towels and clothing pressed in tightly, but an occasional lurch off a wave ensured the items lost their well-packed security.

It was time for me to act. I clambered on deck as the seas rose further, and the wind began to howl and scream. Rain was falling hard. I had to reduce sail. I didn’t bother with wet weather gear. I would’ve only had to dry it. I wore my usual sailing kit: cotton knickers and Indian shirt. My clothes were drenched in seconds. They stuck to my body. My short dark hair was plastered against my skull. Water, both fresh and salt, was running in rivulets down my face and chest and back.

I was wearing a harness securely attached to the boat, but I wore it reluctantly because it restricted my movements on deck. I was twenty-seven and immortal, even sitting in my fear. I believed in the strength of my arms and my capacity to hold on by both hands and feet. To balance. To keep safe.

I slid my bottom along the coach roof. I couldn’t walk upright in the rolling chaos. My feet were braced at every new step. I could do this! I moved my body slowly – carefully, one foot at a time into the next secure space.

Releasing the main halyards, I hauled down the sail. I leaned my hip into the boom as I furled the heavy sailcloth and tied a lashing around the boom, the sail, and the gaff.